Over the years, I’ve been increasingly aware of what one could call a deficit of compassion in medical care, and have observed the effects not only on patients but also on clinicians, and even on the institutions in which clinicians serve. I felt moved to find a better way to train clinicians in compassion, and to do this, I had to better understand compassion.

Traditionally within psychological science, compassion has been defined as “a benevolent emotional response toward another who is suffering, coupled with the motivation to alleviate their suffering and promote their well-being.” This standard definition reflects the idea that compassion has two main components: the affective feeling of caring for one who is suffering, and the motivation to relieve that suffering. While this perspective makes sense intuitively, I am going to suggest that this conventional definition of compassion might have limitations.

A Tribute to Francisco Varela

Any insights I might share on enactive compassion would be incomplete without acknowledging the tremendous contributions of Mind & Life Co-founder Francisco Varela. Francisco embodied in his life, work, and disposition the integration of neuroscience, Buddhism, and philosophy. Also present throughout was his great humanity, as well as his sense of the relationship between justice and compassion.It was while attending a science and humanities meeting in Cadeques, Spain in 1981 that Francisco and I engaged in robust conversation around dharma and science. Out of these conversations emerged the idea for more formal dialogues between Buddhism and Western science, and the early seeds of Mind & Life were planted.

Over the years that I knew him, I witnessed Francisco grow the enactive view of mind. The basic idea of the enactive approach is that “the living body is a self-producing and self-maintaining system that enacts or brings forth relevance, and that cognitive processes belong to the relational domain of the living body coupled to its environment” (The Embodied Mind, 2016 Revised Edition). On this view, human beings continually engage in “sense-making”—not just in our thoughts, but also through our actions in the world, which are always both situated and embodied.

Francisco’s perspective on enaction has deeply affected how I see my own work in end-of-life care, and more generally compassionate action.

The view of compassion outlined above differs from one that I came across in Francisco Varela’s writings years ago (see text box). He says, “It should not be surprising… that one of the main characteristics of spontaneous compassion, which is not a characteristic of volitional action based on habitual patterns, is that it follows no rules.” What he suggests here is that compassion is not a feeling per se, but an emergent process arising out of our lived experience in a spontaneous manner. That is to say, rather than compassion being a discrete internal feature that can be trained like a muscle is trained, this view holds that compassion is a process that is emergent, unpredictable, dependent on context, and therefore what Francisco might call “enactive.”

From this perspective, compassion can be seen as an emergent process in a dynamic, adaptive, and precarious relationship between mind, body, and the lived environment. It arises spontaneously from the ground of a number of interrelated attentional, affective, somatosensory, and cognitive processes that are, in turn, embedded in and responsive to the larger context (e.g., physical, social, cultural). Perhaps we can say that a person who is compassionate enacts the world he or she is embedded in, and this world reflects social, ethical, and political values that elicit and shape the emergence of compassion.

Roshi Joan describes compassion as an emergent process at the 2014 Mind & Life Dialogue with the Dalai Lama,

“Mapping the Human Mind.”

From a Buddhist perspective, compassion has three forms. Drawing from the fourteenth century Zen teacher Muso Soseki, the first of these is common or referential compassion. This is compassion in relation to a so-called object of suffering, usually someone or a situation that is characterized as an in-group person or being, or a context of familiarity. Most of us experience compassion toward those with whom we share close connections—our parents, children, spouses, siblings, and our pets, maybe even the old trees in our yard. We also tend to feel compassion more readily for our friends, colleagues, neighbors, and members of our own culture or ethnic group. We may feel a stronger connection with those who have suffered in ways that we ourselves have experienced. Referential compassion may also extend beyond the circle of our familiars to include those whom we don’t know, such as victims of sexual harassment or police violence, or the unsheltered and refugees, where there is some kind of empathic resonance. It can also extend to creatures and places.

The second form, insight-based compassion, is ethically and dharmicly grounded. This kind of compassion is more conceptual but also points toward some kind of realization. Soseki’s discussion focuses on the realization of the truth of impermanence and dependent co-arising. From my perspective as a contemplative and caregiver, insight-based compassion also encompasses the understanding that compassion is a kind of an ethical imperative—turning away from suffering can have negative consequences for self, other, society, and the world. For example, when we see someone in need, ideally we feel compelled to act. We don’t just walk by. We don’t feel indifference or moral apathy. Responding to suffering with compassion is the “right” thing to do, an affirmation of respect and human dignity. Still, even in this second category of compassion that Soseki describes, there is a self and an other… there is an “object” that compassion is projected onto.

A third form of compassion described by Soseki is non-referential or universal compassion—that is, compassion without an object. Soseki posits that the third category is actually what is genuine compassion, as it is a continuous unfolding responsive process in our lived, contextually embedded experience. I believe that this is what Varela was referencing in the quote above: a spontaneous non-volitional response to suffering, with no thought to self or other, or even ethics, though we could say that the outcome is ethical. As one Zen koan from the Blue Cliff Record puts it: “it is like adjusting your pillow at night.”

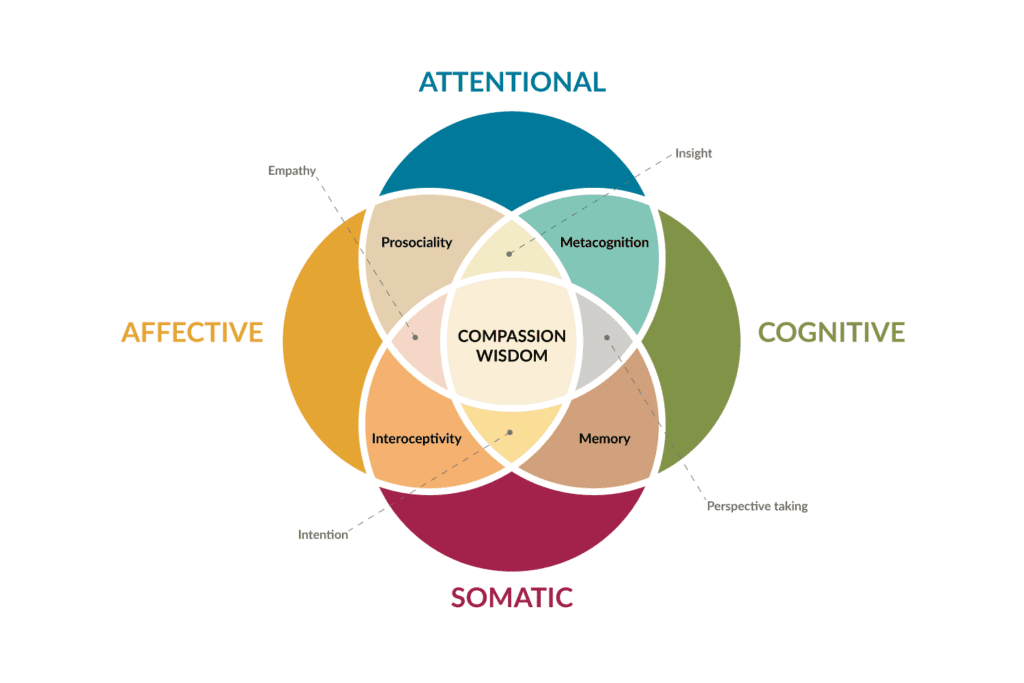

In my own work on what I have tentatively called enactive compassion, I isolated four interdependent modes that braid, prime, and optimize the emergence of compassion (see figure 1). I developed this map to more fully explore compassion, drawing on work in neuroscience, social psychology, Fransisco Varela’s ideas, and my own experience in the end-of-life care field, and as a contemplative. The key components of this framework include 1) attention and attentional balance; 2) prosocial affect, like concern and caring as well as altruistic intention; 3) a cognitive domain related to unprescribed insight; and 4) embodied processes that prime ethical and engaged responses to the presence of suffering, in relation to lived experience embedded in the moment and in the world.

What I am suggesting is that compassion is an emergent process arising out of the interaction of a number of interdependent somatic, affective, cognitive, attentional, and embodied processes unfolding in the context of our whole and situated lived experience. There is no compassion without attentional and affective balance. Compassion is not possible without altruistic intention and insight. And compassion is an embodied, embedded, and engaged process that is enacted in the world, and is spontaneous and fundamentally unprescribed. To put it simply, compassion is made of non-compassion elements and is fully context dependent. Training in these non-compassion elements through contemplative practice can help lay the foundation for compassion to emerge spontaneously.

In this podcast episode, Roshi Joan shares how our minds are enactive,

and elaborates on compassion as emergent and dependent on context.

Why do I sense that the enactive view might be important in relation to understanding compassion? Because many consider compassion from a narrow neuro-centric perspective or simply from a religious or psychological perspective. I believe that the enactive view might bring greater depth to our understanding of our response to suffering, not as an activity pattern in the brain or a psychological moment, but as a sense-making process that is a richly woven fabric, that folds and unfolds itself moment after moment in our full and inclusive lived experience. Especially in light of the grave challenges facing humanity today, now is the time when cultivating the qualities of compassion is essential to the survival of all species, and our planet. As Evan Thompson said: “Living is sense-making in precarious conditions.” I would add: Compassion is sense-making in precarious conditions.

Have something to share? Email us at insights@mindandlife.org.

Support our work with a gift to Mind & Life.

The Mind & Life Institute

The Mind & Life Institute