In 2014, the evening before a much-anticipated meeting with the Dalai Lama, it was tough to sleep. Throughout the night, I woke up feeling anxious. I had never presented to a global leader, let alone someone I held in such esteem. I knew sleeping would help me feel prepared. I also knew I was unlikely to be judged harshly by one of the kindest human beings on the planet. Still, this knowledge was no match for the worries that consumed me. Ironically, or poignantly, helping people navigate their emotions was the topic for the meeting. Whether I liked it or not, I was doing some last-minute ‘me-search’ on the power of emotions.

The following day, I arrived a bit sleepy at a grand hilltop hotel overlooking the San Francisco Bay. The lobby was full of eager visitors, and I wondered how many of them had also laid awake last night. I already knew sleep had evaded the person next to me, my pioneering emotion scientist dad, Paul Ekman. He was now meticulously reviewing our presentation, which proposed an online atlas of emotions.

As we waited, I reflected on events leading up to this sleepless morning, beginning nearly 14 years earlier with the 2000 Mind & Life Dialogue on Destructive Emotions. This dialogue brought together influential scholars, scientists, and practitioners to explore Buddhist and contemporary scientific approaches to emotions, especially how to manage our unhelpful, destructive responses to difficult emotions (like laying awake from senseless worry).

The intimate gathering took place over four days in the picturesque hill town of Dharamsala at the foot of the Himalayas. The presenters included Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard, neuroscientist Richie Davidson, biologist and Mind & Life co-founder Francisco Varela, and developmental psychologist Mark Greenberg, among others. Daniel Goleman skillfully moderated the meeting and then wrote a book about it entitled Destructive Emotions. I joined that meeting as an observer, a guest of my dad, who was also a presenter. That meeting was potent with discussion and ideas. Collaborations formed there, catalyzing a series of studies1, books, and a contemplative training program called Cultivating Emotional Balance.

Before the 2000 meeting, my dad, who already had a distinguished career, was considering retirement and had been skeptical about what he could learn in this forum to integrate scientific and Buddhist wisdom. Instead, he found himself profoundly changed by the experience, professionally and personally, and joined early efforts to advance contemplative science around emotions. I grew up professionally upon the shoulders of this work. I have based my research, teaching, and consulting within the field of contemplative practice and science, specifically relating to emotional awareness and well-being.

Reflecting over the last two decades, I am struck by the range of applications for understanding our emotions, whether as an intervention to prevent burnout for health professionals, or a means to educate students to build healthy relationships that support learning. There’s no question that emotions can dramatically help or hinder us in leading productive, purposeful, and compassionate lives. Yet we are not born with clear instructions on how to work with them.

Studying Emotions

In 1872, Charles Darwin proposed a theory of emotions derived from his observations of humans and animals. He theorized2 that emotions had an evolutionary purpose for survival and were universal among humans and animals. He experimented on the power of emotions at the London Zoological Garden by placing his face upon the sealed glass habitat of a poisonous puff adder snake. Darwin tried not to flinch when the snake lunged toward the glass. He discovered that “knowing” he was safe couldn’t override his fear response. To this day, evolutionary psychological theory suggests that our emotions operate outside of our conscious awareness to help us respond to immediate threats and challenges before we have time to think (thus making Darwin recoil in fear even if he ‘knew’ he was safe).

Contemporary social and cognitive emotion science includes more sophisticated means of replicating Darwin’s first-person experiment tracking how our bodies and minds respond to threats and opportunities. Both objective biological and subjective self-report measures are needed to study emotion. Biological measures include fMRI brain scans, which identify brain structures closely linked to the feeling of emotions, including the amygdala, insula, and a structure in the midbrain called the periaqueductal gray. The prefrontal cortex can help regulate these parts of our emotional brain. Heart rate variability and electrodermal activity can capture the immediate bodily response to our emotions through our autonomic nervous system.

The field has learned much about the brain and body during emotion from experiments that record these biological measures3 while evoking emotion through salient images or films (a laboratory equivalent to Darwin’s snake), or engaging people in stressful tasks or difficult conversations. The MIT Media Lab recently piloted a wearable electrogastrography (EGG)4 to record gut-related emotional state changes. It’s important to note that all current biological measures are considered “blunt” instruments, meaning they can’t offer specificity about what types of emotions we feel or how this could relate to other aspects of our thoughts, memories, or desires. Thus, biological measures are significantly strengthened with the complement of self-report—having participants share their subjective descriptions of their feelings.

Facial expression can also be measured to capture emotion. A 2015 study published by Cliff Saron and colleagues used facial expression and self-report measures to compare participants as they watched heart-wrenching media about a traumatized soldier. Those who learned meditation were able to resonate strongly with the emotion of sadness but had less reactive facial expressions. The authors concluded5 that meditation training may help us manage our emotional distress but not eliminate our emotions.

My favorite method for emotion research is Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA), a self-report measure deployed through smartphones to capture the richness of our emotions throughout the day. This method contributed to a classic study by Killingsworth and Gilbert. In this study, they asked 2,250 participants at different points throughout the day to log their current state of happiness and whether their mind was wandering; results6 showed a relationship between negative mood and mind wandering. And EMA goes beyond a laboratory tool; many popular publicly available apps offer a chance to track and monitor mood. A recent review of these apps surveyed users and found that identifying emotions and patterns of feelings helped people manage their daily moods and mental health symptoms and improve well-being. Using technology to track and log our emotions is good for research, and also seems to be good for our well-being.7

Over the past forty years, emotion research has blossomed. Multiple scientific journals and conferences are dedicated to this area, and as can be expected, we don’t have all the answers yet. One ongoing debate relates to the fundamental nature of emotions, and how they arise in our minds and bodies. One side of this debate posits that emotions come from the ‘bottom up’— we feel sensations in our body and construct an emotion label and a story about our sensations based on our personal history and our brain’s predictions of what will happen next. In this theory,8 our emotions are not universally the same across people, but are shaped heavily by context and past experience.

The other side of the debate has researched universal aspects of specific emotions, what triggers them, the physical signatures of those emotions, and likely responses to them. In this universal theory of emotion, all humans share a fundamental set of emotions, some of which have distinct vocal and facial signals. The expression of these universals, and even the words we use to describe them, is influenced by our culture. Different models9 suggest that humans share from 7 to 27 distinct emotions.

Overall, these issues are key areas for ongoing investigation, and both approaches provide valuable insights we can apply in building emotional awareness. Whether we identify emotions through their embodied sensations or with specific terms like frustration, jealousy, and joy, we can increase our emotional awareness by labeling our emotional states and becoming curious about what causes our emotions.

Contemplative scientists have shown10 repeatedly that meditation training supports emotion regulation. Emotion regulation is a term used to describe our effortful, intentional strategies to modulate emotions, as well as our bodies’ often implicit strategies to regain calm, such as a deep breath or sigh, that happen outside our conscious awareness. Emotion regulation strategies include what is called cognitive reappraisal (reframing our experience), emotional granularity (specifically labeling and identifying our emotions), meta-awareness (becoming aware of our emotions), and response modulation (suppressing or hiding our emotional reactions).

As you might imagine, the ability to regulate our difficult emotions profoundly contributes to our well-being. Meditation strengthens11 emotion regulation through developing attention, present-moment embodied awareness (interoception), an attitude of openness and acceptance towards our experience (whether good or bad), decentering (less fixation on our experience), and cultivating insights about the roots of our emotions and goals of our emotional lives. Cultivating positive mental states and savoring what feels good is another key aspect of meditation that goes beyond regulating the difficult. Emotion awareness, a term drawn from early dialogues with scientists and the Dalai Lama, encompasses many strategies of emotion regulation developed through meditation, with an overarching perspective on how our emotions relate to the greater meaning of our life.

“…the ability to regulate our difficult emotions profoundly contributes to our well-being.”

Mapping our Emotions: A Sample Exercise

Since 2010, I have co-led Cultivating Emotional Balance (CEB), a contemplative science-based training co-created by Buddhist scholar, author, and teacher Alan Wallace and my dad. Over the years of teaching about emotions across many populations, one constant is how difficult it can be for people to control or understand their emotions. In CEB, one of our primary tools is an emotion episode timeline. With the timeline, we bring more awareness and understanding into our often unconscious experience of emotion.

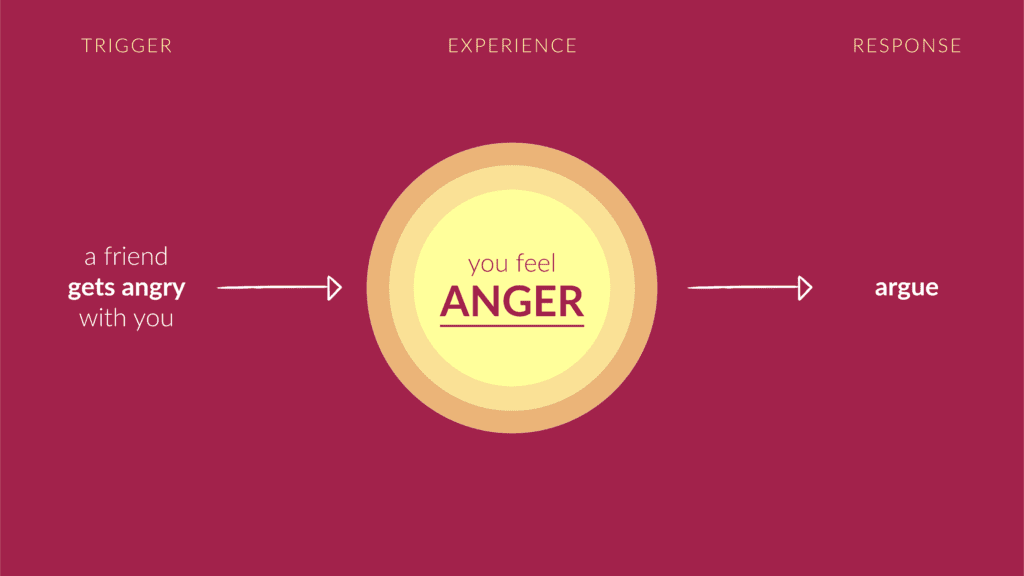

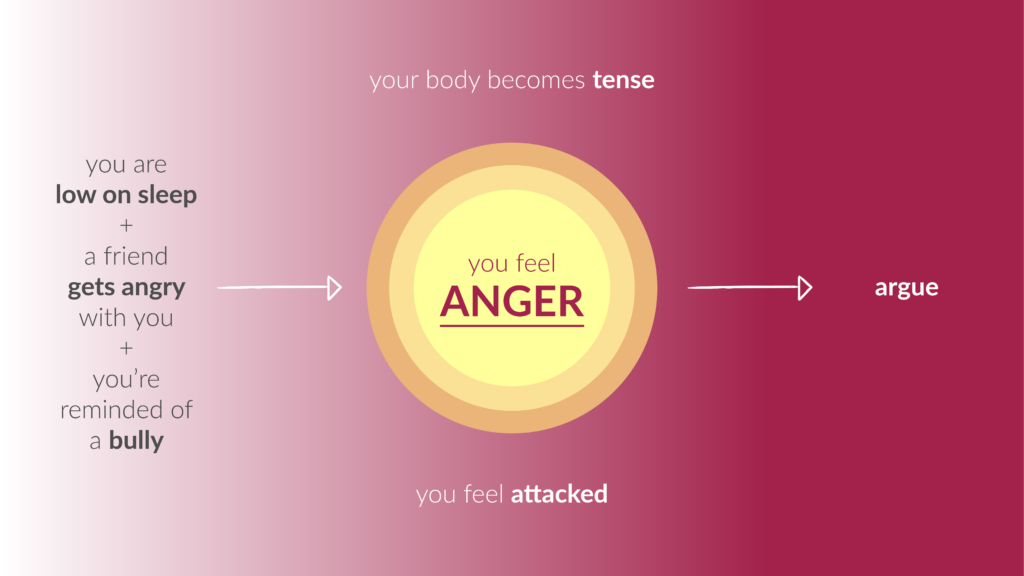

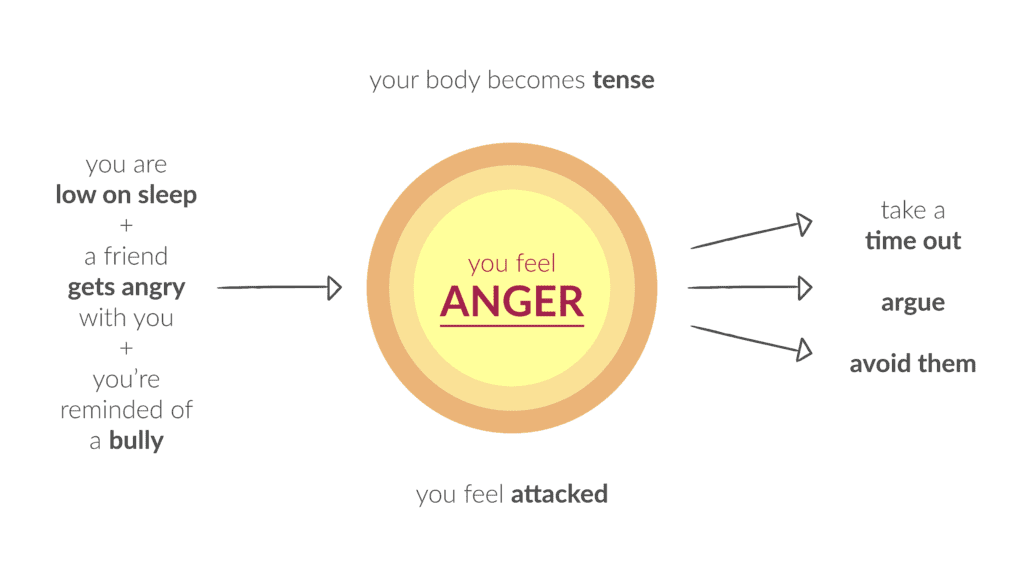

Using the illustrations below we will map an emotion episode, something you can try on your own with any emotion. The timeline shows that emotions are a process; emotions are not unidimensional experiences of “I feel good” or “I feel bad.” Instead, emotions unfold over time with a trigger, experience, and response, all of which we learn to see more clearly through developing our attention.

Trigger. This first image shows a simple timeline of getting into an argument with a friend. In this case, ‘a friend getting angry with you’ is the triggering event.

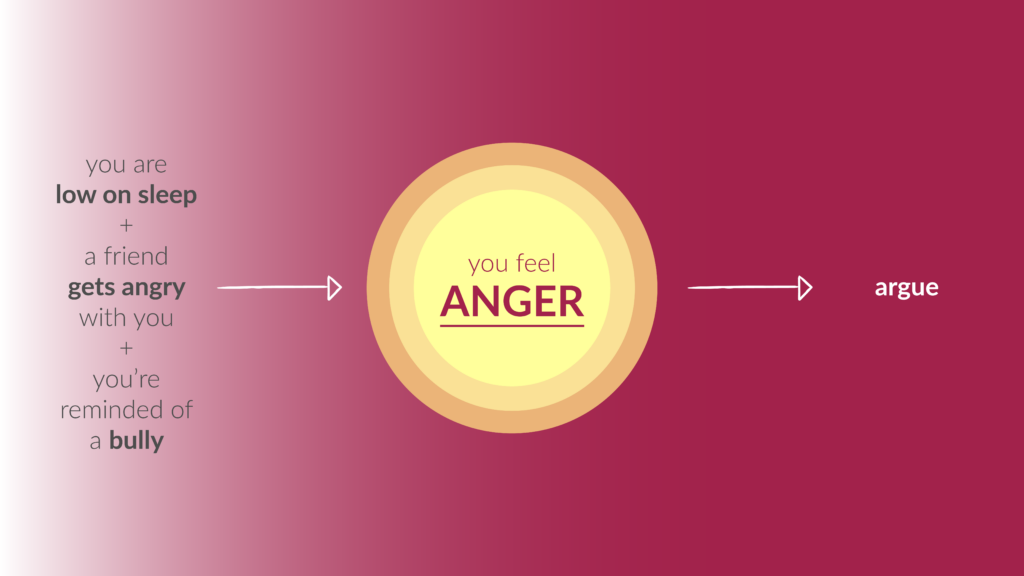

If we bring more awareness to the trigger (indicated by the background getting lighter), we see we are low on sleep. Poor sleep makes us more reactive, and having strong emotions can get in the way of proper sleep. Additionally, adequate sleep can help us process our daily stresses and emotions. Insufficient sleep12 is what we call a precondition of the emotion. Our bodies can influence our reactivity and send signals we may interpret as an emotion—a tight stomach can be anxiety or a bad burrito.

The last aspect of our trigger relates to what’s called the theory of automatic appraisal. According to this theory, we are constantly appraising our environment based on previous potent emotional experiences stored in our memory, our perception database. We often get into trouble because matching a pattern of what happened in the past to what is happening now is only sometimes accurate. Yet that is what our brains naturally do, and they do it approximately. In the example here, we may project a past emotional experience of a bully into our current appraisal of a friend who is annoyed with us, and thus be unable to see the situation clearly.

Both modern science and Buddhist psychology agree that we cannot entirely rid ourselves of this nearly automatic appraisal. However, Buddhist practitioners have demonstrated that we can learn to become more aware of and transform our appraisal system through consistent practice13. Through training our attention, we can distinguish what we are experiencing from what we are projecting. This is a form of meta-awareness, recognizing thoughts as they arise. Our pre-condition and perception database influence our response to the triggering event. If our appraisal didn’t include a bully but was influenced by a memory of being abandoned, we might feel sadness instead of anger. If we weren’t tired, maybe we wouldn’t feel such strong emotions.

Cognitive reappraisal is one essential emotion awareness strategy that targets these nearly automatic beliefs with a counter perspective. A positive reappraisal of this emotion could be “I am upset because I care about this friend” or “I feel compassion for my friend and myself at this moment.” In addition to reappraisal, taking good care of our bodies with sleep, nutrition, and exercise will help us curb emotional reactivity.

Emotional experience. The yellow circle of anger represents the impact of emotion on our embodied and cognitive states. When we are triggered, physiological, psychological, and behavioral changes can arise in one 25th of a second. In the example above, we feel tension in our bodies and have thoughts related to our emotions, such as feeling attacked.

Another effective emotion regulation strategy is developing embodied awareness through meditation. As we practice, we gain familiarity with the changes in our bodies as we encounter different sounds, sensations, sights, smells, tastes, and thoughts. If we learn to pay attention to the body, we may notice the sensations before we consciously experience the emotion. Focusing on our bodily sensations when we feel disappointed or annoyed may also help us decenter from the thoughts related to our emotions—those thoughts will usually add more fuel to the fire. From the example above, thinking about feeling attacked will undoubtedly increase the intensity of our experience.

Through the “handshake with emotion” practice, Buddhist teacher Tsoknyi Rimpoche encourages people to turn toward the felt sensations of emotion in the body, and become curious and open to watching the sensations as they exist and slowly subside, without an agenda. I’ve found this practice can help me meet and release my difficult emotions by focusing on the sensations, instead of the story of my emotion. Developing this genuine, curious attention toward our emotions—even the difficult-to-feel emotions like rage or shame or loneliness—is a critical step in developing distress tolerance.

As mentioned earlier, simply naming or labeling our emotions also helps us with decentering. Multiple studies have shown that labeling our emotional experience reduces the strength of our felt emotions, impacting our body by slowing our heart rate.

We often frame our emotions as bad or good, positive or negative. From the contemplative science lens, there are no bad, negative emotions. We can respond to any emotion in ways that are harmful and destructive, or helpful and constructive. Our anger can lead to social action; our joy could make us gloat.

Response. Our immediate response to emotion can occur within seconds, and our more deliberate response may take minutes. The immediate response in this timeline is to argue, which will likely result in more difficult emotional episodes. Destructive responses like arguing are usually unhelpful for our own and other’s well-being. Constructive responses, like taking time out to get some space, support greater well-being. Avoiding someone, the other response shown here, is an example of an ambiguous response to our emotions, because it may be constructive or destructive depending on the context.

When we are in the grip of our emotions, it is as if we are wearing emotion-colored glasses. Many emotion regulation strategies aim to help us take space and have time for a new perspective that is not so colored by our immediate feelings. Mapping an episode, as demonstrated here, can help identify where and how we might apply strategies and encourage curiosity about how our emotions show up for us. The Atlas of Emotion provides further examples of how the same trigger of “a friend getting angry with you,” coupled with different content in the perception database and preconditions, can lead to emotion episodes of fear, sadness, disgust, or enjoyment.

Towards Equanimity and Purpose

While our media-saturated culture may have us believe that we should always feel positive and good, research shows that experiencing a full range of diverse emotions is associated with well-being. Our ability to recover from difficult emotional experiences is a hallmark of emotional resilience and flexibility. Our emotions are not a problem, but sometimes our reactions to these emotions can be a problem.

The Four Noble Truths, a core teaching of the Buddha, points out that the root cause of difficulty stems not from the challenges in our life but from getting stuck in emotional reactivity to life’s inevitable struggles. This reactivity often stems from the core belief that someone or something causes our emotional response. If we think emotions are a response to the world outside, we will look for solutions outside. If we understand the role of perception and projection, we can begin to compassionately investigate the sometimes painful stories and experiences from our past that influence our present experience.

Once we recognize that past memories influence some of our reactivity, we can have more empathy for others who are expressing difficult emotions unskillfully. If we become committed to emotional awareness and balance, we become less interested in what happened and why, and the daily changing circumstances that impact our emotions feel less personal. This worldview is one of equanimity, an ability to meet the good and bad in the world and in others with an even heart. Equanimity is more possible when we can see the roots of our emotions more clearly.

There is no specific word for emotion in Buddhist psychology. In Buddhism, craving, hatred, and delusion are destructive mental states, lasting longer than a temporary emotion and giving rise to our destructive emotions and behaviors in the world. The most advanced approach to work with these destructive emotions is to cultivate a mental state of open awareness through meditation, in which the emotions untangle themselves without any deliberate strategy. This may sound far-fetched, but we can practice by trying to experience emotion simply as a feeling wave in the body.

“The most advanced approach to work with these destructive emotions is to cultivate a mental state of open awareness through meditation…”

In many forms of Buddhism, the purpose of meditation is to cultivate an enduring state of genuine happiness, sukkha, with the explicit goal to then support not only our immediate friends and family but all beings. Temporary feelings of happiness or a reduction in stress may arise as part of meditation training, but this is not the goal.

Contemporary psychology and Buddhist psychology are not irreconcilable points of view; in fact, there is a lot of meaningful overlap between the two. The Dalai Lama saw the potential for collaboration during that 2014 meeting in San Francisco. “The very first travelers by sea needed maps to explore the world,” he said, adding “to explore a calm mind, we need a map of our emotions.” The Dalai Lama was delighted with the proposal for creating an atlas of emotions and the potential benefits such a map could offer. He insisted that the map reflect contemporary science and understanding.

In order to provide an accurate picture of the science, we completed a survey of top researchers in the field of emotion. Based on their responses, the Atlas unpacks five families of emotions (anger, fear, disgust, enjoyment, and sadness) exploring common experiences, responses, and strategies for emotion regulation. Given the prevalence of technology in daily life, we created the Atlas of Emotion to be a visually engaging online educational experience. The site launched in 2016 and has been translated into six languages. Work to improve and enhance the contents of the Atlas is ongoing.

In my research and teaching on emotion awareness, I have learned how essential it is to adopt a perspective in which every emotion is a learning opportunity. Every emotion carries an important message about our needs. Emotions are not a problem, or a solution for temporary relief, but a way of aligning with a greater purpose in life. By holding this perspective while reflecting on the causes of our emotions, we may feel less embedded and cognitively fused with them. This doesn’t mean we’re detached or aloof, but that we have more room to see the complexity of our emotions, and their temporary nature. This perspective shifts how we respond to our emotions, and what might trigger emotions in the first place.

Learning constructive ways to approach difficult emotions is as important as ever before. In 2021, Mind & Life hosted a 20-year anniversary of the Destructive Emotions meeting in which the original participants were joined by new voices. An underlying theme throughout the anniversary meeting was a message the Dalai Lama has long shared with scientists: it is time to apply the science directly to people’s lives.

Clearly, learning to work with our emotions can have many benefits to us as individuals, helping with mental struggles, relationships, and more. In addition, the wisdom and science of emotion awareness are directly relevant to the social issues of our time—this includes trauma stemming from systems of oppression and inequality, fear of scarcity which prevents generosity towards global citizens seeking refuge, emotional distress over our climate, and more.

Our emotions are fundamentally relational. When we feel connected we are naturally emotionally regulated; when we feel lonely or threatened our autonomic nervous system is on alert and we will be reactive. The Dalai Lama recently said, “We have no more time to worry about our differences, we must be kind, and act as brothers and sisters, all 8 billion of us.” Developing greater emotional awareness, along with embracing the reality of our interconnection, will enable us to choose compassionate responses to our current global challenges. Such responses may well be our only effective solution.

Notes

- 1.

Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J., Ricard, M., & Alan Wallace, B. (2005). Buddhist and psychological perspectives on emotions and well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(2), 59-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00335.x

- 2.

Darwin, C., & Prodger, P. (1998). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. Oxford University Press, USA

- 3.

Levenson, R. W. (2014). The autonomic nervous system and emotion. Emotion review, 6(2), 100-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073913512003

- 4.

Vujic, A., Tong, S., Picard, R., & Maes, P. (2020, October). Going with our guts: potentials of wearable electrogastrography (EGG) for affect detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (pp. 260-268). https://doi.org/10.1145/3382507.3418882

- 5.

Rosenberg, E. L., Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., Aichele, S. R., Jacobs, T. L., Bridwell, D. A., & Saron, C. D. (2015). Intensive meditation training influences emotional responses to suffering. Emotion, 15(6), 775. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000080

- 6.

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932-932. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192439

- 7.

Caldeira, C., Chen, Y., Chan, L., Pham, V., Chen, Y., & Zheng, K. (2017). Mobile apps for mood tracking: an analysis of features and user reviews. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings (Vol. 2017, p. 495). American Medical Informatics Association. [Full Article]

- 8.

Posner, J., Russell, J. A., & Peterson, B. S. (2005). The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Development and psychopathology, 17(3), 715-734. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050340

- 9.

Cowen, A. S., & Keltner, D. (2017). Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 114(38), E7900-E7909. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702247114

- 10.

Hill, C. L., & Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion, 12(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026355

- 11.

Farb, N. A., Anderson, A. K., Irving, J. A., & Segal, Z. V. (2014). Mindfulness interventions and emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 548–567). The Guilford Press.

- 12.

Vandekerckhove, M., & Wang, Y. L. (2018). Emotion, emotion regulation and sleep: An intimate relationship. AIMS neuroscience, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2018.1.1

- 13.

Kral, T. R., Schuyler, B. S., Mumford, J. A., Rosenkranz, M. A., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Impact of short-and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. Neuroimage, 181, 301-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.07.013

The Mind & Life Institute

The Mind & Life Institute