It was accident and curiosity that led Dr. James H. Austin to a moment of awakening one day in 1974, in the form of a red Japanese maple leaf. He was in Japan, meditating in a centuries-old Zen temple, when he entered into a not-quite-sleeping, not-quite-waking state.

Jim was relatively new to meditation, having begun only a few months before quite by accident. A distinguished neuroscientist specializing in pediatrics who held several academic appointments, Jim was in Japan for a sabbatical at the Kyoto University Medical School. On the flight over, he read a book given to him by a friend, “Zen in the Art of Archery”. Curious, he had sought out an English-speaking Zen teacher and began an intellectual inquiry and a personal meditation practice.

That day in the temple, he reflects, “When I next became aware that the world existed, I found myself in blacker than black atmosphere … and this space I awakened into had in the top left corner a very vivid Japanese red maple leaf, dangling. Extraordinary sight. It was completely silent. I had no physical sense of self.”

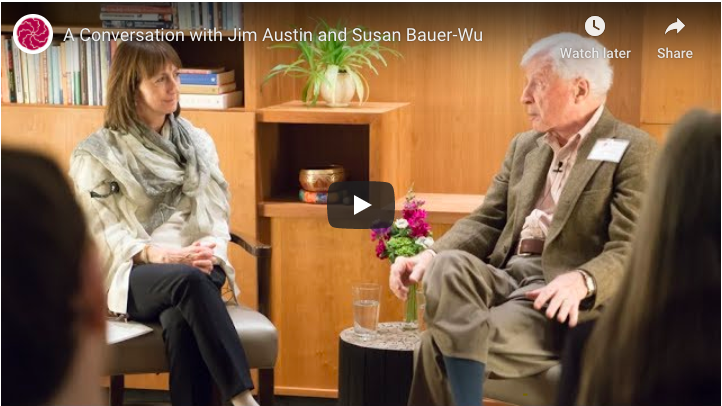

Jim is telling the story to staff and invited guests gathered at the Mind & Life Institute in Charlottesville, Virginia, for a special evening program in early November. He must have recounted this event a hundred times over the years, yet he seems to marvel still at the mystery of that moment. Here was a man who studies the brain, whose brain was undergoing something completely outside of anything he’d ever studied.

“Literally I was hallucinating, blind, had lost all my usual sense of hearing and was involved in this huge space that had no end. And this was pretty impressive. It convinced me, as a neurologist, that this was something neurologists needed to learn about.”

He’s not stopped learning, or meditating, since. One of the figureheads of the contemplative sciences in the west, Jim has studied the correlations of brain chemistry and mindfulness for almost half a century, teaching, speaking and producing an impressive bibliography of work. His first book, “Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness”, published in 1998, is a nearly 1,000-page tome dense with neurological research woven with his personal accounts of Zen training that is considered an essential roadmap for scientists and practitioners alike.

“Jim is a pioneer in contemplative sciences whose seminal writing continues to be referenced today. He’s a brilliant thinker with a long standing meditation practice, and is one of the most delightful, modest people I know. We are honored to host him here in Charlottesville,” says Mind & Life president Susan Bauer-Wu, a long-time friend and colleague of Jim, who has taught Mind & Life seminars for many years.

At 92, with thick white hair, kind blue eyes and a sure gait, he possesses a memory that most 50-somethings would envy. His conversation flows effortlessly between the days of wandering monks in India and China 2,000 years ago and the most current MRI technology tracking the neurological oscillations that define one’s consciousness. He’s still writing, traveling and lecturing. His secret? “Choose your parents wisely,” he quips. He eats right (low fat foods, white meat versus red), plays tennis, works out at his local gym in Columbia, Missouri, and in the years since his wife passed, he has found a new life companion. And he credits his meditation practice, citing studies that suggest meditation plays a role in slowing the brain’s aging process. “The bottom line message—if you’re not already meditating, it’s not too late to start.” Jim was about 50 when he saw his maple leaf.

The central concept of Jim’s investigation is the physiology of the interplay between the sense of self (ego) and other (from the Greek “allo”). MRI data of normal brain waves, he says, suggest that the more one focuses on self, the less one can be open to the “other.” And opening to the other—the universe beyond one’s own skin—is where awakening occurs. External stimuli—a beautiful sunset, a work of art, a poem, even a simple maple leaf—draw the brain’s attention away from self.

For the Zen practitioner, the stimulus is breath. “Attention on breath is therefore key in meditating to quiet the self,” Jim says. He believes the capacity for awakening lies within each of us, but is drowned out by constant signals from the limbic system, the part of our brain that controls emotions, among other things. “This over-conditioning of our fears, our wants, our longings and our loathings … reinforces the psychic and somatic sense of self and makes it want to dominate the world.” The more self-centered the person, the more he or she suffers, and creates suffering around himself or herself.

A question from one of the Mind & Life guests about teaching mindfulness to young people prompts Jim to contemplate the future. Students the world over are learning meditation in school, and classroom behavior is often improved, he claims. On the other hand, children are growing up in an “iPhone environment,” occupied by screens and selfies and social media that are guaranteed to make them more self-centered, he says. This is setting the stage for a “physiological struggle for your kids and my kids and all kids. And I’m afraid that the outcome of the present planet will depend on how that balance is struck and how successful we are at educating generations of students to be better meditators. Huge, huge issue.”

There’s a pause. A long pause. Fifteen seconds tick by as everyone in the room ponders this.

“Well, that’s a sobering note to end on; I feel I ought to bring out a toy.” From his coat pocket, he produces a brightly painted wooden figure of Bodhidharma. It’s weighted on the bottom so when it’s knocked over, it rights itself. He says that by playing with this toy, Japanese children learn the maxim: “Seven times down, eight times up.”

It’s a simple lesson from an ancient Zen master bearing profound implications for the future.

Watch the full conversation below: