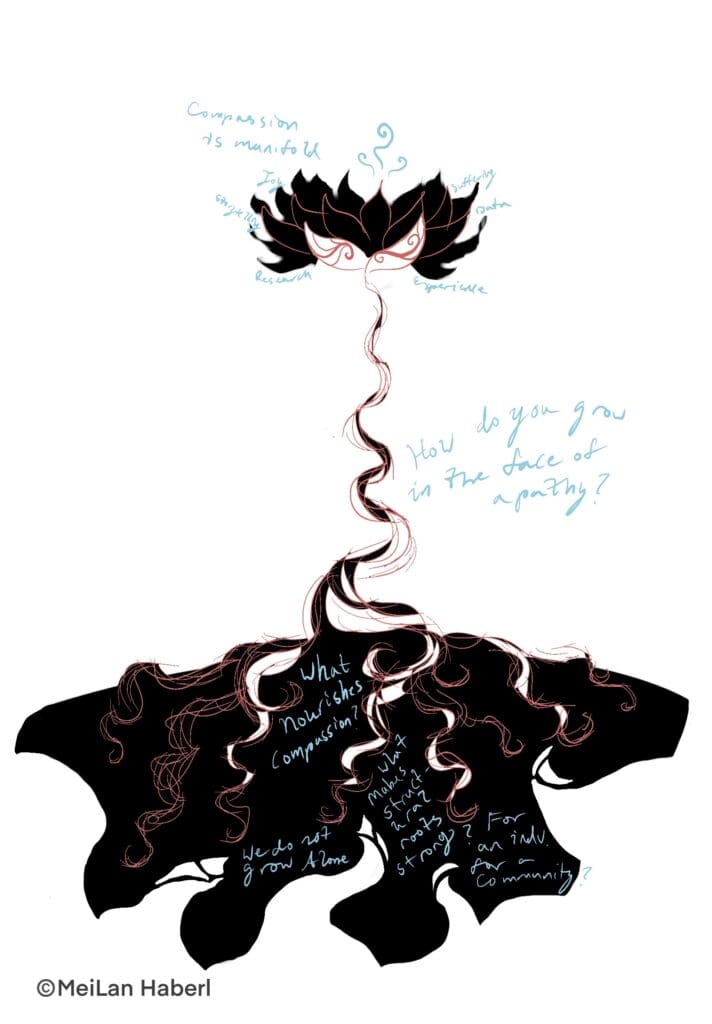

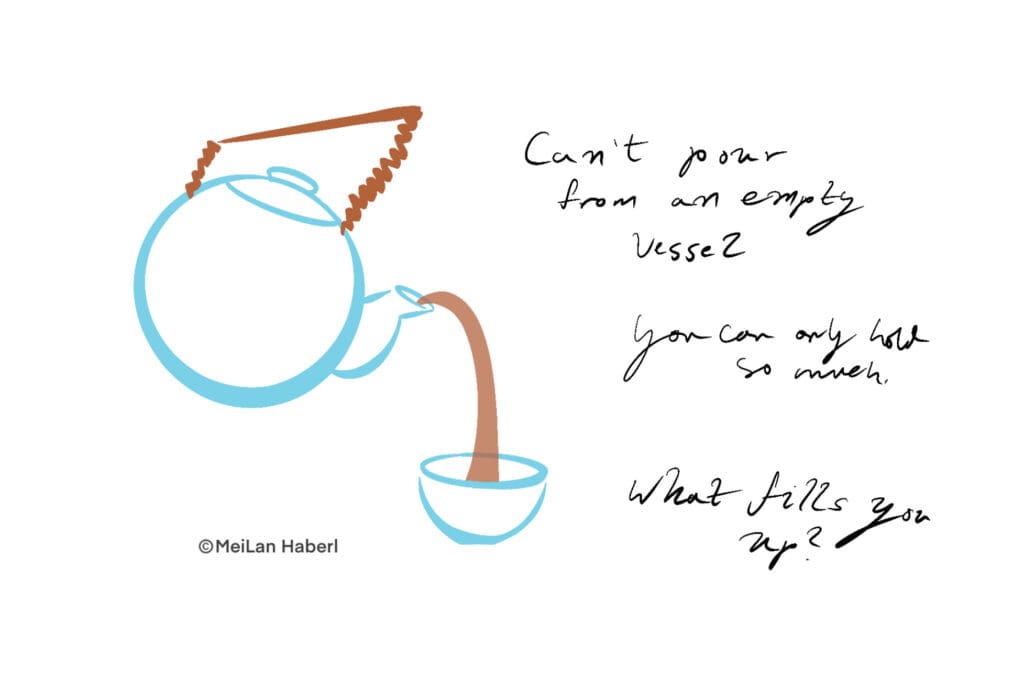

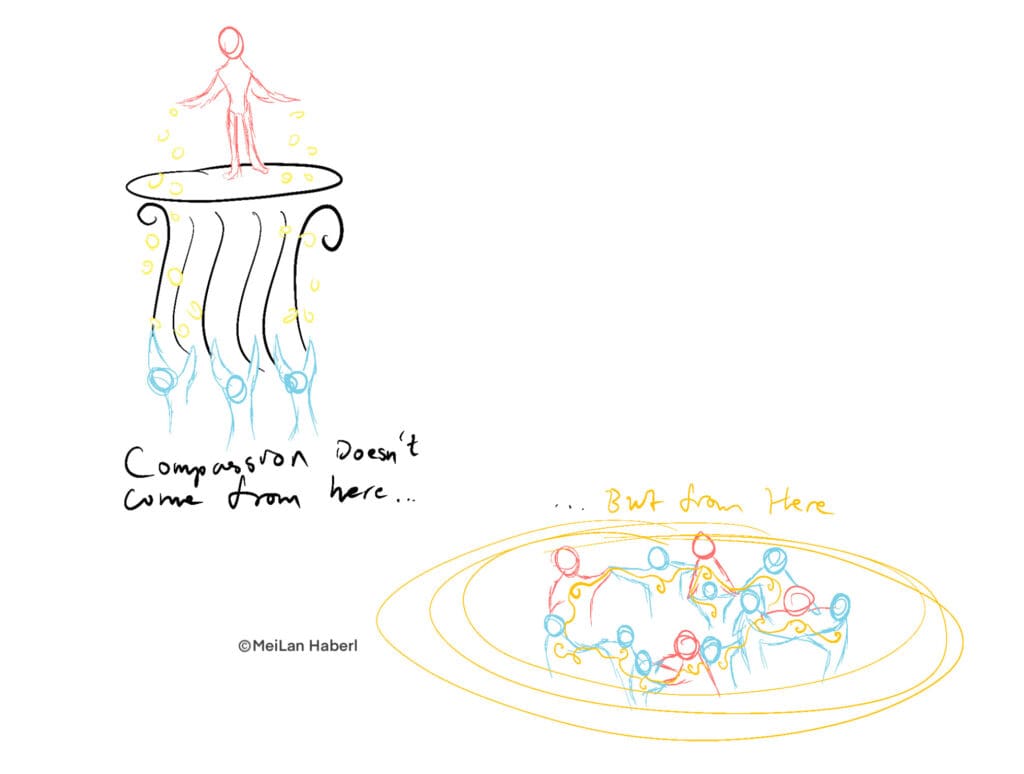

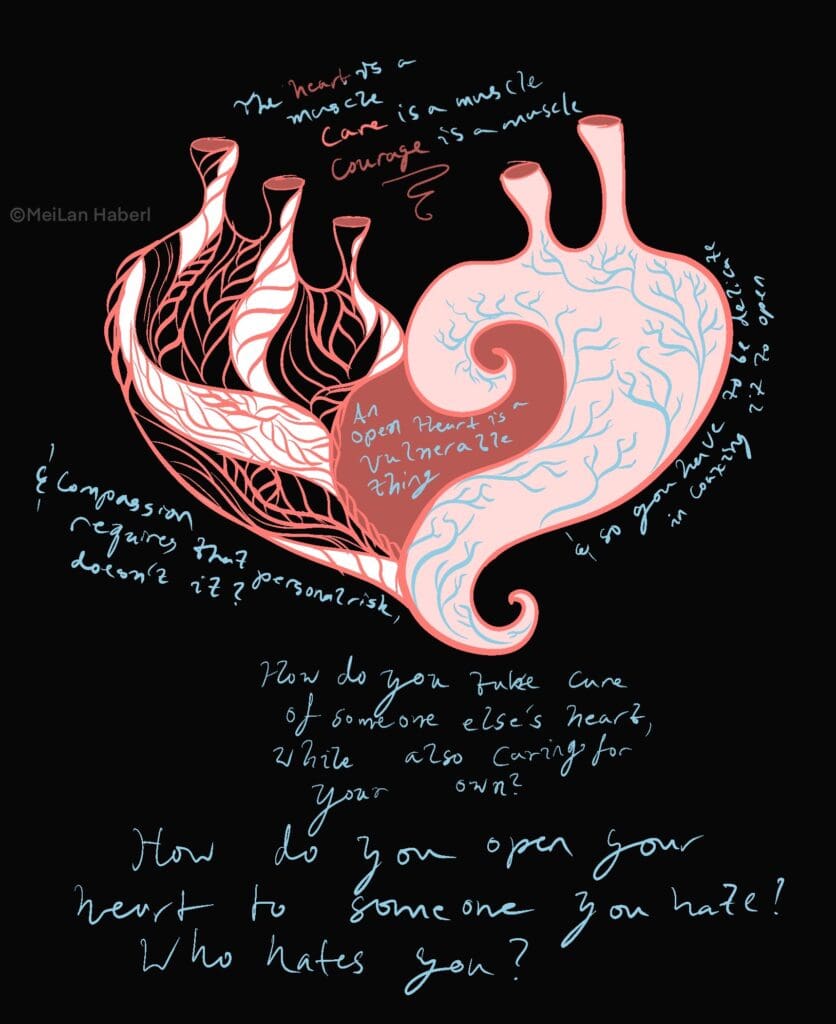

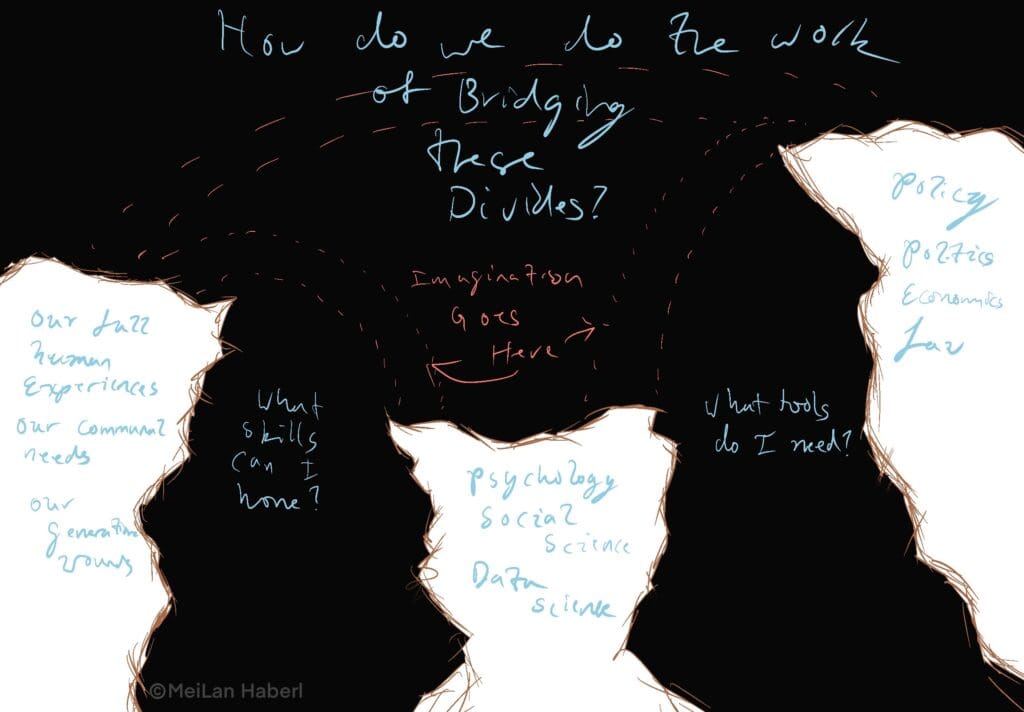

The Mind & Life Summer Research Institute (SRI) is a collective experience in which all members bring their individual experiences together to build a community. This personal reflection, from the 2024 SRI held June 2-8 at the Garrison Institute, is but one perspective of many. Because I am a visual thinker, this piece includes digital sketches I created as I processed the event—inspired by conversations, contemplation, and questions that arose throughout the week.

At college, especially as an undergraduate, a week can pass in the blink of an eye—seven days blurring together in a haze of classes, rushed meals, random encounters, work, stress, sleep. Far too much happens far too quickly to fully register, let alone process.

At the Summer Research Institute (SRI), a week is a saga. Like a day at college, a day at SRI is packed with happenings. But the lessons—not just those planned and presented by the official speakers, but every insight gleaned in informal conversation with others—unfold not in a haze, but through mutual discovery. The meals are savored hours for mindful connection, rather devoured in a rush. Encounters are made something more than random by the unique vulnerability that characterizes an SRI conversation. Rather than simply “meeting,” we instead arrive, together, whole.

When I attended the SRI for the first time in 2023, the uncharted territory of encountering other attendees was my greatest anxiety. I had never been to an academic conference before. I was one of the youngest participants in the ‘emerging’ scholar category. Moreover, I had squeaked off the waitlist. I had no idea what I was doing.

Even with a previous year of SRI experience, that spark of imposter syndrome is never fully extinguished. Everyone at SRI is stunned that we were selected to attend—because everyone else around us is such a wellspring of wisdom, hard-earned insight, and incalculable experience. We all have moments of feeling that we are out of our respective depths. The beauty of SRI is the invitation to dive in at that deep end—to forgo the banal shallows of small talk and let go of the insulation of titles, degrees, career fields, and nationalities. Participants are left to choose—to meet one another exactly where we are, ask difficult questions, answer honestly, set aside preconceptions, and listen openly. The invitation to connect authentically was especially true under this year’s theme of Awakening Compassion in Times of Division.

“The beauty of SRI is the invitation to dive in at that deep end—to forgo

the banal shallows of small talk and let go of the insulation of titles,

degrees, career fields, and nationalities.“

Twenty-three years is not a long time to be alive. But it is long enough to have seen the rise of 21st century fascists spouting the violent rhetoric of the 20th century, survive a global pandemic that continues to kill, and grow up inundated with front line social media coverage of war and genocide around the world. Not once in those 23 years has this planet suffered from an overabundance of compassion.

This SRI, then, felt almost like stepping into another world, a world characterized not by militant anxiety, entrenched hostility, and ivory tower hierarchy, but a community invested in writing a different story.

This story is one of care.

Over the course of the week, I heard so many participants remind one another: “self compassion is also compassion.” I repeated this mantra as I stumbled to my room on Tuesday in need of a nap. American civil rights activist Audre Lorde writes, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” This is one of the only places where I have seen people move without hesitation to make space for others to preserve themselves, to ask “what can I do to help?”

This story is one of discomfort.

You gain nothing from the SRI if you do not first allow yourself to open, to be vulnerable. In one session, a courageous participant takes the mic and shares devastating childhood trauma—not in the interest of accruing pity, but to ground the conversation beyond abstractions of the healing power of compassion, to ask hard questions from the close up and gritty work of giving compassion to someone who has caused you grievous harm, rather than remaining comfortable in a distantly altruistic perspective.

This story requires an investigative interweaving of the personal and the scientific, a balancing of lab-based and empirical narratives with the lived and felt data we carry within us. Keynote neuroscientist Molly Crockett described how “engineers and scientists desperately need training and conversations with scholars in the humanities and practitioners, because no single way of thinking about the world… is going to be sufficient.” Dr. Crockett spoke stirringly of the collaboration required to meet head-on dystopian AI prophecies that herald the superiority of machine-learning algorithms over flawed human beings. When we turn incautiously to AI as a replacement for people, we “define a certain narrow type of compassion that can be programmed into a machine… but compassion and wisdom and understanding are not something that can be extracted,” she said.

This technological dismembering of our humanity is perhaps a reflection of an inhumane vivisection we already enact, systemically, in the siloed institutions of academia and industry. “I have been regularly dissuaded as a scientist from speaking my personal story,” shared neuroscientist Sará King in a panel on “Compassion in Action.”

“I was losing everything I have ever worked for,” she said, “because as a scientist, you are told you’re there to focus on the data, as if the data doesn’t have anything to do with you.” She admitted to feeling the kernel of hatred embedded and ignited by this denial of one’s complete humanity, the sense of dehumanization that festers when we treat people as capital to be extracted from an organic context and forced to perform a specific function…like a machine.

How do we, then, work, to then re-humanize ourselves? Dr. Crockett advocated for the “embodied communion” of physical human connection, while yoga teacher and mindfulness coach Oneika Mays encouraged participants to confront “reductive views of humanity.” In describing well-meaning efforts to support the displaced, novelist and essayist Dina Nayeri emphasized the importance of giving help “without taking away dignity.” For health researcher and educator Liz Grant, it’s a question of “employing imagination” to dream and build a world that is more humane, more inclusive, more compassionate.

These are all crucial lessons and practices to keep in mind as we move through a painfully divided time. They can also feel frustratingly abstract, when deep compassionate work requires struggle, discomfort, grappling.

“…deep compassionate work requires struggle, discomfort, grappling.“

I don’t yet know how to take all this and put it into practice, how to answer the questions I am left with after this conference. But Sará King offered a guiding light: “The fact that you exist makes you an expert in your own life, right? So if we learn to treat fellow human beings in this way and involve them as experts in our research, then we are going to have so much more of a vast repository of data from which we can pull.”

While I cannot hope to capture all the brilliance of the myriad experts I met at SRI this June, I can share some of the most human moments and amazing people I learned from.

On one afternoon, a soccer game unfolded between Tibetan monastics, PhDs, and undergraduates from around the world. In that moment, baptized by rain, all were on the same team.

During an interfaith panel that contained many voices, accents, and culture-specific idioms and anecdotes, each speaker reinforced a shared understanding, a shared care.

Late one night, new and older friends offered me shampoo advice, a moment that transformed into an unexpected experience of opening up and feeling not just seen, but cared for in the days that followed.

Midway through one session, a new friend took the mic, owning up to a moment of implicit bias, infantilization, and dismissal of a panelist of color. There was no request for absolution, but an apology and a call to others to keep up this work, inside and out.

Listening with wonder as one participant gracefully and conscientiously led a contemplation on how to grapple with genocide on distant shores.

Feeling Reggie Hubbard’s gongs echo through the vast hall, resonating deep in my bones, reverberating with everyone else in the space.

Putting down perfectionism to struggle, mess up, and learn about a dozen styles of dance from around the world in a spontaneous movement party with a group of new (and far more coordinated friends.)

Having speakers who are of the Global Majority, who are openly LGBTQ+, who are from walks of life beyond academia, be honored on stage. It was deeply moving and heartening to bear witness to as a queer person of color who often wonders what voices are being left out of a given conversation.

Learning from audience members the art of asking skillful, compassionate questions—that nevertheless challenge on matters of race and inclusiveness in empirical research.

Sharing something in a small group that brings someone else to tears. Holding them in the aftermath.

The joy of a queer affinity group lunch. Taking time to celebrate Pride.

Seeing friends from last year’s SRI—changed over the course of a week in 2023, changed again by 11 months apart, changing still at this conference. Experiencing the extraordinary privilege of learning to love them, exactly as they are, again. Let me take a moment to slow down, to see you, to hear you, arriving in this moment.

These are the seeds. These moments I will carry back to college, back into the world, carefully. I do not know when or how they will grow. But somewhere in the mayhem, the division, I will do my own small part in cultivating compassion.

MeiLan Haberl is an undergraduate at Yale University, where she is an RA at the Social Perception and Communication Lab. She is majoring in psychology, and is projected to graduate in December 2024 with a Bachelor of Science.

Please note that the views and opinions shared in this article are those of the author(s) and may not necessarily represent the official stance of the Mind & Life Institute. We appreciate and encourage diverse perspectives within our community.