Filmed during Mind & Life Institute’s “Mind & Life XXVII: Craving, Desire and Addiction” on October 31, 2013.

Day Four: Contemplative Perspectives

World religions have developed their own conceptions and responses to the important issues around desire. This day’s dialogue examines Buddhist and early Christian views on the nature of desire, how it becomes problematic, and practices that can help us work with it in productive ways. Buddhist monk, scientist, and scholar Matthieu Ricard begins the day by offering a Buddhist perspective. Christian theologian Wendy Farley discusses reflections from the Beguine tradition in the afternoon session.

From Craving to Freedom and Flourishing: Buddhist Perspectives on Desire

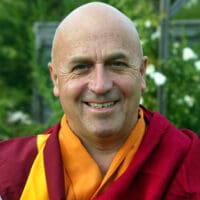

SPEAKER: Matthieu Ricard

A vast and selfless aspiration can be the source of the greatest human qualities and accomplishments; an egocentric aspiration offers no guarantee of genuine satisfaction. Desire is natural, and it plays an essential role in helping us to realize our aspirations. Yet, it is a blind force that is capable of either providing inspiration to our life or poisoning it. Desire degenerates into a “mental toxin” as soon as it becomes craving, obsession, or unmitigated attachment. Craving is all the more frustrating and alienating in that it is out of sync with reality. When desire becomes a pervasive craving, we become addicted to the very causes of suffering. Afflictive mental states also tend to distort our perception of reality, preventing us from seeing it as it really is. Craving idealizes its object; hatred demonizes it. This misapprehension opens a gap between the way things appear and the way they are. On the other hand, states of mind such as selfless love reflect some understanding of the intimate interdependence of beings and our happiness and that of others-a notion that is attuned to reality. Experience shows that craving gains in strength when repeatedly allowed to take its course, just as the more salt water one drinks, the thirstier one becomes. Once we reach a stage of mental and physical dependency, craving feels more like servitude than pleasure. We lose our freedom. It does not follow, however, that we need to stifle our emotions. Preventing them from being expressed while leaving them intact, like a time bomb in a dark corner of our mind, is an unhealthy solution. We need to establish the right dialogue between our intelligence and our emotions to prevent afflictive emotions from proliferating and invading our mental landscape. Buddhism teaches three principal ways of dealing with craving and other negative emotions. The first consists of applying a direct antidote to craving. The second allows us to free ourselves from craving by not identifying with it but instead looking straight at it and letting it dissolve in awareness as soon as it arises. The third uses the raw power of emotion as a catalyst for inner change. The choice of one method over another will depend on the moment, the circumstances, and the capacities of the individual. All share a common aspect and the same goal: to help us stop being victims of afflictive emotions.

Contemplative Christianity, Desire, and Addiction

SPEAKER: Wendy Farley

Based on texts from 12th-century Beguines (contemplative laywomen) and 4th through 7th-century desert ascetics (early monastics), Farley offers an early Christian interpretation of desire and craving. Contemplative Christianity recognizes healthy and diseased forms of desire. In its unhealthy form, desire becomes a kind of craving, somewhat cognate to addiction. The ego, tormented by anxiety and craving, encounters the world as a (meretricious) promise of relief and happiness. Strategies to use the world to satisfy desire objectify others and tend toward self-destructive forms of relief. Negative mental habits (anger, vainglory, anxiety, lust) take root in the mind, not as passing emotions but as enslaving constituent structures, often hidden from consciousness. In contrast, healthy desire displaces both the object and structure of craving. Desire is no longer oriented toward ego centric satisfactions but turns toward absolute, unconditional love [agape]. Agape is simultaneously other than the self (God) and the deepest truth of the non egocentric “self.” Non-egocentric desire for agape disenchants the ego and opens awareness to the nondiscursive dimension of mind. This opening places mind on its “throne of peace” (non-attachment) and reorients to others as subjects of sympathetic joy and compassionate concern. Desire to participate in agape is a powerful antidote to craving. Healing of diseased desire is sought through watching the mind, meditation, contemplation, and compassionate practices. Remembering the luminous love that is one’s deeper identity counters the addict’s self-loathing, contributing to recovery.

INTERPRETER: Thupten Jinpa

PANELISTS:

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama

Kent Berridge

Sarah Bowen

Richard J. Davidson

Vibeke Asmussen Frank

Roshi Joan Halifax

Marc Lewis

Nora Volkow

Diana Chapman Walsh

Arthur Zajonc