Mind & Life periodically invites guest writers to contribute their perspectives and experiences to the blog as a way of deepening dialogue and understanding around key themes related to our mission.

What is it about mindfulness practice that underpins such diverse positive outcomes? And aside from less-tangible notions of awakening, what supports the widespread intuition that mindfulness is transformative for society?

Since 2014, the Mindfulness Initiative has worked to answer these questions in our efforts to support politicians across the world in understanding how mindfulness can inform public policy. An impressive body of studies now reinforces the use of mindfulness-based interventions in the context of diverse problems from chronic pain and depression to relationship conflict and discrimination. From a policy perspective, influencing decision-makers often requires the ability to change specific, measurable outcomes. The strength of findings around mindfulness has allowed for successful policy advocacy in several areas, including health, education, criminal justice, and policing.

While research findings are encouraging, they can also limit the public imagination around mindfulness in an important way. Pre-existing conceptions of why one might practice necessarily shape the research agenda. Scientists measure what they think will change, which then limits the kind of applications that can credibly be considered by policy-makers and government administrators (who exist in already siloed sectors of public life). When mindfulness champions extrapolate beyond the existing evidence, they may be accused of magical thinking.

To bridge the gap between researchers and public advocates, we suggest a better framework for talking about mindfulness as a foundational psychological capacity in meeting the challenges of our time. The common factor across the positive outcomes of mindfulness is its contribution to agency, or the capacity for intentional action, both individual and collective. This framework bridges the missing middle between the instrumental evidence and more radical claims, offering a bigger “why” for mindfulness that we hope will help scientists to ask the bigger questions.

The common factor across the positive outcomes of mindfulness is its contribution to agency, or the capacity for intentional action, both individual and collective.

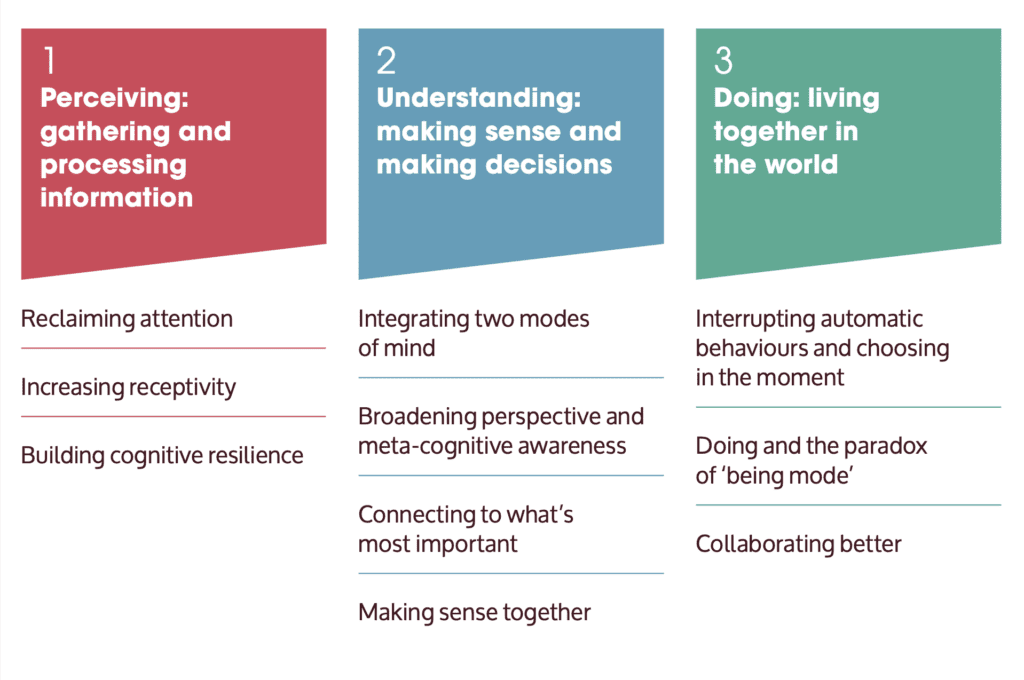

Synthesizing evidence from across the mindfulness field, our new discussion paper proposes a model of agency based upon three interacting dimensions: perceiving, understanding, and doing. In everyday life, most of humanity operates on the assumption that these three dimensions function effectively and in a linear manner—that we are collecting information from the world, fashioning knowledge from it, and acting rationally based on this intelligence. In reality, a host of factors in both the body and our cultural environment can interrupt this process. Content on social media, for instance, is increasingly fine-tuned to trigger our primal threat systems or baser impulses, which can distort our perceptions and shape behavior in ways that are misaligned with our deeper values or intentions.

The particular value of mindfulness is in its contribution to each of these dimensions of agency when our ideal processes are interrupted, improving the conditions for intentional and collective action when we need it most. We outline this frame briefly below.

Perceiving

In the perceptual domain, we examine attention, the ancient and modern forces that hijack it, and the emancipatory possibility of attention training. Exploring the attitudinal qualities of mindful awareness like openness, curiosity, and care, we show their role in processing and filtering information.

Understanding

Regarding understanding, we explore the large-scale cultural dynamics that complicate our individual and collective efforts to make sense and make decisions at all levels of society. We look at evidence that mindfulness supports perspective-taking, cognitive flexibility, collective intelligence, and re-orienting to our deepest values, which cultivates a world view that can hold complexity at the level needed to understand systemic issues.

Doing

In the sphere of action, we return to familiar territory for mindfulness practitioners: the problem of automatic behavior and the possibility of restoring intention as a driver of doing. Here we come to the critical importance of collective action, and the role of mindfulness in fostering our innate capacity for collaboration. Mindfulness practice is not passive. Indeed, the greater the urgency, the greater the need to slow down and tune in to real-time information, values, and intention.

In offering this analysis, our intention is not to establish a definitive view, but rather to advance a dialogue on the value of mindfulness within the sphere of human agency and social change. As such, we’re genuinely indebted to the critics of the field whose work has galvanized us to account for common misunderstandings of mindfulness and its effects.

Mindfulness alone will not solve the world’s problems. But in our complex and hyper-connected world, we face both grave challenges and extraordinary opportunities. Humanity is not at leisure to design, build, and test every solution we will need from scratch—and the existing popularity of mindfulness in governments, workplaces, and communities should not be lightly dismissed. By building on this momentum we can strengthen our collective capacity to act well. We have never needed it more.

To learn more, please visit the Mindfulness Initiative website, or contact: jamie@mindfulnessinitiative.org.uk.