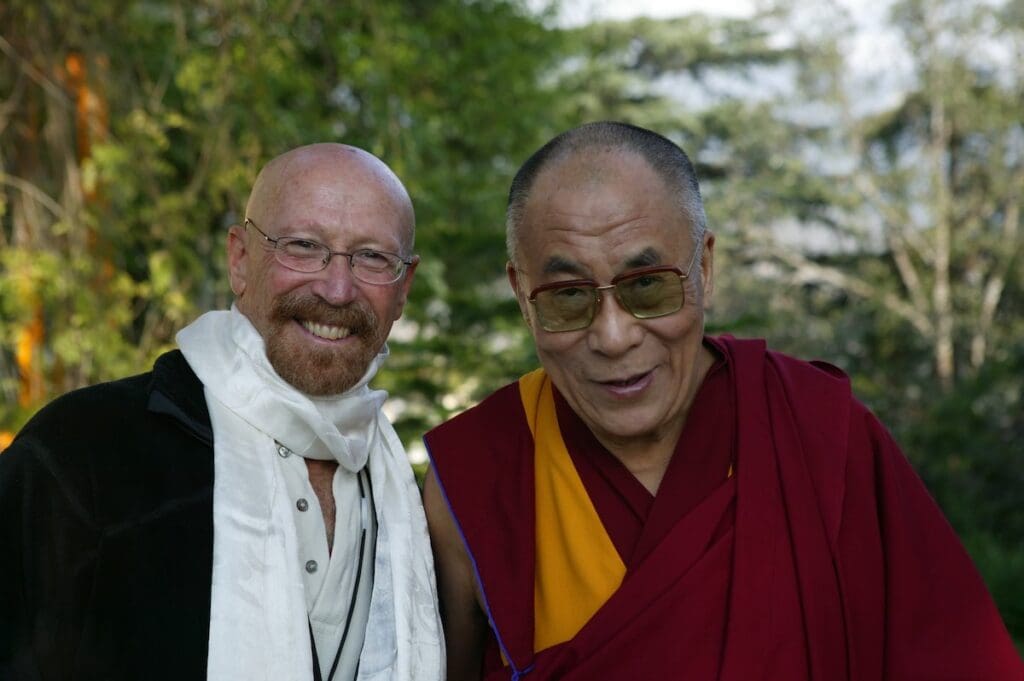

The first Mind & Life Dialogue with the Dalai Lama took place in Dharamsala, India in October 1987 on the theme of Buddhism and the cognitive sciences. Five scientists gathered with His Holiness in what was described as a ‘living room conversation.’ For seven days, they explored topics ranging from cognitive psychology, perception, memory, and the development of the brain to causality and karma.

At the time, no one knew that an organization would eventually emerge from this unique bridging of contemplative wisdom and Western science, or that the first seeds would be planted for what would become a new field of research now known as contemplative science.

Over its first two decades, Mind & Life’s work evolved in two distinct phases. The first pioneered dialogues focused on the historic coming together of Buddhist contemplative inquiry and modern Western science. Both systems had similar goals: understanding the nature of reality and using that understanding for the benefit of humanity. The difference was methodology. While science traditionally took an ‘objective’ approach, looking from the outside in (a so-called third-person perspective), contemplative traditions like Buddhism relied on rigorous subjective inquiry, examining the mind from the first-person perspective through introspective practices like meditation. Prior to the Mind & Life Dialogues, these two epistemological methodologies had no organized way to share their approaches and discoveries. From this early phase of Mind & Life’s work emerged numerous books and collaborations—along with a growing sense of possibility.

A Vision for Humanity

As the dialogues evolved so, too, did an understanding of the promise that lay in investigating the human mind and building a knowledge base around how the mind works. A second phase of Mind & Life’s work began emerging in the late 1990s, driven by the question of how to achieve greater real-world impact for the benefit of humanity.

The science advisors to Mind & Life suggested pursuing a research agenda. Along with that came the aspiration of applying research findings to alleviate human suffering and promote flourishing. The Dalai Lama had noted with great interest the fixation in the West on physical fitness and physical hygiene and the absence of mental fitness programs.

Recognizing that the ubiquity of physical fitness programs in the West came about largely as a result of scientific research demonstrating the health benefits of regular exercise and physical training, we wondered whether such an approach could be used to foster mental fitness and emotional wellness. At the time, medical and psychological research was largely focused on diagnosing and treating mental illnesses. Comparatively little research existed on what people could do to develop positive mental states.

This inquiry gained momentum at the beginning of the 2000 Mind & Life Dialogue on Destructive Emotions when the Dalai Lama challenged participants to explore the efficacy of contemplative practices in cultivating positive emotional states—and based on evidence-based research, to find ways to teach such practices in secular environments.

Building a Research Field

We formally launched the research program in 2003 at the first public dialogue, Mind & Life Dialogue XI: Investigating the Mind: Exchanges between Buddhism and the Biobehavioral Sciences on How the Mind Works, with more than 1,200 people—researchers and the lay public alike—attending on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

This was a turning point for Mind & Life and the inquiry that started in the late 1980s. The excitement was palpable—it seemed very possible that we could create a legitimate research field focused on contemplative science. The question was how. In search of a roadmap, we had investigated the origins of other scientific fields from quantum physics to genomics. Many emanated from close-knit convenings at research institutions, where ideas could be shared, debated, and advanced. It was clear we had to engage not only veteran researchers, but up-and-coming graduate and postdoctoral students who could see new investigative pathways and career possibilities through an emerging field. We would need to bring such individuals together in an immersive, multidisciplinary environment where they could learn from and share ideas with one another. This was how the concept for Mind & Life’s Summer Research Institute (SRI) took shape.

As we closed the MIT public meeting, we announced the formation of the first SRI in June 2004 at the Garrison Institute in upstate New York, where it was hosted for 17 consecutive years until the COVID pandemic necessitated an online alternative.

The intention behind the SRI was to create a level-playing field for both emerging researchers and veteran faculty members. Everyone ate meals together; they talked openly during breaks and engaged in contemplative practices, including a daylong retreat. We wanted to transcend the traditional academic hierarchy. Many leaders in the field today look back on the SRI as the place where their contemplative research careers began, and where they found their ‘academic home.’

While SRI created fertile ground for idea-sharing, deep inquiry, and relationship-building, we also knew that researchers would need funding to pursue their ideas. With the support of a visionary donor, we launched a research grant program at the SRI, awarding a total of ten $10,000 grants in 2004. Two years later, this research grant program was renamed the Francisco J. Varela Research Grants. The grants sought to fund rigorous examination of contemplative techniques with the goal of gaining greater insight into contemplative practices and their application for reducing suffering and promoting flourishing.

Fast forward to today and the recipients of the Varela Grants—and other Mind & Life grant awards—have helped lay the foundations for the field of contemplative science, leading to groundbreaking applications in areas such as education and mental health. Cumulatively through its grant programs, Mind & Life has awarded more than $6.5 million to over 290 projects in 21 countries. As a result, grantees have gone on to compete successfully for over $130 million in follow-on grant funding from other sources.

What had seemed like an unusual (and academically risky) endeavor in those early days has now blossomed into a vibrant and mainstream line of inquiry. The chance we took on nurturing a new field through creating a safe and generative space for researchers to gather, and making funding available for leading-edge investigation, has proven fruitful many times over. As Mind & Life takes stock of its 35th anniversary, there is much to be grateful for—and much to celebrate.

Adam Engle is a co-founder of the Mind & Life Institute, serving as Chair and CEO from 1987 until his retirement in 2012.