During her recent visit to the Mind & Life offices in Charlottesville, social neuroscientist Dr. Tania Singer spoke as much about the heart as the brain.

Singer is the director of the Department of Social Neuroscience at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany. She is on the board of directors of the Mind & Life Institute and, in 2015, published “Caring Economics: Conversations on Altruism and Compassion, Between Scientists, Economists, and the Dalai Lama”.

Singer was invited to share the latest insights from the ReSource Project, an impressive, large-scale longitudinal study on which she’s the principal investigator. The goal of this research is to assess the effects of mental training on subjective wellbeing, health, brain plasticity, cognitive and affective functioning, the autonomic nervous system, and behavior.

The study included more than 300 participants and a 9-month mental training program with three distinct parts. Over the course of the project, participants were repeatedly assessed using more than 90 measures including behavioral experiments, blood tests for stress hormones, and MRI brain scans.

The scale and rigor of the ReSource Project are impressive, but maybe more remarkable are its aims.

Singer’s integrative approach endeavors to address large, societal questions using the tools of psychology and neuroscience. Can changes in the brain contribute to a more peaceful and democratic world? Might meditation practice combat economic and environmental crises? If individuals can increase their capacities for altruism, might social systems and institutions also be changed for the better?

To begin to answer these questions, the ReSource Project tested three different modules of meditation-based training methods, each focused on developing a distinctive mental or emotional capacity. Or, as Singer says in conversation, “cultivating the mind and the heart.”

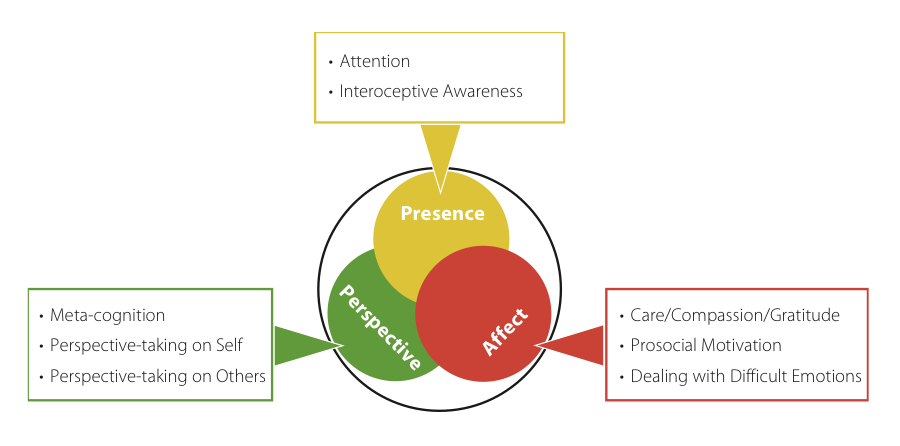

One module, called Presence, focused on introspective awareness and attention. Meditation practitioners will be familiar with exercises such as attending to one’s breath and performing an attentional body scan.

Another module, Affect, focused on building compassion as well as dealing with difficult emotions. Training included loving-kindness meditation from the Buddhist tradition.

The third module, Perspective, focused on meta-cognitive skills—or “thinking about thinking”—and theory of mind, the capacity to understand that other people may have different beliefs and perspectives than oneself.

Participants trained in all three modules (each lasted three months), but in different sequence. This eloquent design allowed the researchers to examine the effects of each training specifically, while also looking at changes over time in the same people.

Singer and her team measured cortical thickening—places in the brain where there was more grey matter than there had been before. One of the most intriguing sets of findings came from the Affect module. After three months of this meditation-based training in compassion, brain scans of study participants revealed changes in a network associated with socio-emotional processing. Thus, the pattern of cortical thickening suggested a possible increase in social and emotional capacity.

To see how these brain changes played out in participants’ emotional experience, the researchers tested the same participants to see how they reacted to watching emotionally distressing videos. This experiment showed an increase in compassion from pre-training levels, suggesting that not only did their brains change, but also their experience in response to suffering. Tests also showed an increase in altruism, the expression of compassion in real-life situations.

During the training, the participants had learned new skills, and this change left physical evidence in the structure of the brain. In this case, it wasn’t a better memory or a quicker response to physical stimuli that had been learned, but a bigger, more vulnerable heart.

In addition, blood tests revealed that these participants had lower levels of cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone, in response to a socially stressful experience. Singer postulated that learning to connect with and have compassion for others might have provided a buffer to social stress for these participants.

This work challenges old ideas about whether or not people can change. “Classical economic theory has for a long time supposed that human traits, called preferences, are fixed and context-independent. The idea was that we were each born a certain way: some are more altruistic, others more egoistic,” Singer explained. “The belief was that such preferences do not change in an individual.”

Singer’s groundbreaking research suggests that not only can traits change, both physically and behaviorally, but they can be purposefully and specifically cultivated with meditation.

For example, Singer found that the three training modules affected cortical thickness in different networks of the brain. Presence training led to increases in cortical thickness in prefrontal regions, areas related to attention. Affect training led to changes in the frontoinsular regions related to socio-emotional processing. And Perspective training caused change in the inferior frontal and lateral temporal cortices, brain structures related to theory of mind.

These findings align with other work suggesting that compassion is associated with a brain network that doesn’t overlap with those for meta-cognition and theory of mind. Similarly, in the ReSource Project, training in attention didn’t change compassionate-related neural networks, or compassionate behavior. The underlying brain structures for these capacities are different, and can be cultivated separately.

During the discussion, Michael Sheehy, Director of Programs at the Mind & Life Institute, commented that meditation doesn’t necessarily have a moral dimension, unless it is intentionally applied to moral questions. Inner calm doesn’t always correspond with compassion.

Singer agreed and pointed out that, in the ReSource study, training introspective awareness and attention before training emotional or meta-cognitive capacities seemed to help those capacities develop when it came time to train them. Inner calm might make compassion come more easily.

The ReSource Project’s findings, and it training protocols, could have wide-ranging impacts and applications. Singer and the Mind & Life Institute staff conversed about the powerful effects of the training methodology used in the study. They discussed how the mental training protocols could be used to grow compassion and an appreciation for people’s differing perspectives in companies, schools, and other institutions.

One of the most effective and novel practices in the study for training compassion and meta-cognition was meditation in dyads: two people sitting across from each other or connected via a specially designed app. In these meditations, one person shares specific aspects of an experience from their day, and the other practices deep listening. “After that practice, participants felt more connected not only to each other, but to other people in the group,” said Singer. “Some people, after doing this dyadic practice for the first time, actually felt very touched because they realized, ‘I’ve never really listened to another person. I’ve just been waiting for my turn to talk.’” Dyad practice seemed particularly related to improvements in stress resilience, which could have implications in a wide variety of settings.

During a public talk and Q&A at the Mind & Life office, Stephen Nachmanovitch commented, “Living within the context of a large society, where someone has deliberately turned up the dial of non-empathy to an extraordinary degree … providing training for the individual might be helpful, but is it putting a Band-Aid on a truly giant problem that is systemic and institutional throughout our society? How might we approach that?”

Singer replied that she’d been thinking about that question for years. “Psychologists are specialists in the individual change business… but for 10 years now I’ve been in cooperation and dialogue with economists, behavioral economists and macro economists, and they talk mostly about change agents like changing the institutional design of a business or institution, changing laws or a whole system,” she says. “We have these two worlds: one in which we think social change can only happen by changing laws, rules and institutions, the other in which psychologists think, similar to Gandhi, ‘You need to be the change you want to see in the world.’ That is, they think that change can only occur by changing yourself as an individual. And I think it is not one or the other, but both worlds need to work together to create transformation by which internal and external change agents are brought together in congruent ways.”

Singer’s work also investigates how social cognition and motivation can explain human social interaction and economic decision-making. This research, funded by the Institute for New Economic Thinking, explores new models of economic decision-making and applies them to global economic problems.

Change, according to Singer, needs to come from the top and from the bottom. The best version of social change is a congruence of individual flourishing and institutional transformation. Those who study the mind must work hand in hand with those that study political organization and economics, so that individual change can have global repercussions.

Watch the full conversation below: